If you’re online at all you likely know that a mass Twitter exodus is potentially at hand, because there’s no faster way to realize that hang on hang on hang on this was not as bad as it could be than when a billionaire stomps in, lays thousands of dedicated people off without notice or severance, and posts incoherent platitudes on what’s suddenly his platform about how he’s giving us all what we need, what we asked for, as though he’s ever talked to any of us when he doesn’t even appear to have spoken to his own (former) employees.

It’s a social media network, and what’s the big deal about that? There isn’t one, objectively, but suddenly we’re acting like the one global town square in existence is about to be bulldozed. We who’ve spent the past varying-number-of-years complaining about twitter are now wailing that Tesla Boy is about to pave paradise and put up a parking lot. Now that we may never “see” each other again, we’ve suddenly realized we were really important to one another. What started as exchanges made of public quips and banter became heartfelt private conversations over direct message. When we didn’t feel our best or most confident, the compliments on photos that we outwardly deemed frivolous did something, gave us something, even if we didn’t want to admit it.

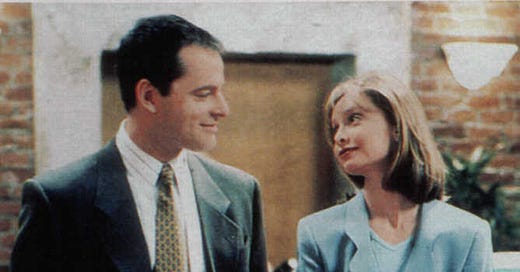

Why’d it do that? I’d say the answer lies where all truly complicated childhood-trama based answers lie: in a 90’s surrealist courtroom comedy TV show. In real time, Ally McBeal was often mocked because its lead character, played almost too endearingly by Calista Flockheart, wore very short skirts. But Ally was a lot more than a traffic-stopping young lawyer. She was truly weird. That she often saw hallucinations of a badly CGI’d dancing baby who shook his diaper to exaggerated cave-man hollars of oooga-chucka oooga oooga was the icing on the cake. She fell so often in early episodes that she once asked, in a voiceover, “Why do I have to always fall down?” Her unregulated emotions often took the form of vivid imaginary sequences wherein she would breathe fire when angry, or lick handsome male guest stars with a gigantic cartoon tongue. She once intentionally rear-ended a guy because they exchanged glances from their respective cars at a red light and it was Valentine’s Day and she saw no other way to ask him out than to meet via exchanging their insurance information. When she found out that the wife of the love of her life was pregnant, she asked the father, “is there any chance it’s…not…hers?”

And for all this, she’s a terrific lawyer, just like everyone at Cage and Fish, the unforgettable law firm in which Ally is, hilariously, not actually the weirdest person there. John Cage, known as one of the best lawyers in New England, is so resplendant with unique quirks that various judges are familiar with them, and Richard Fish, his firm partner, somehow manages to wear his horndog nature and singular fetishes on his sleeve while simultaneously being a genuinely supportive friend to everyone he works with. The associates are a veritable rainbow of Issues, while at the same time seeming like they’d make charasmatic, caring, and deeply intelligent collegues. Like Twitter, Cage & Fish is a place that people who don’t fit in fit in.

Unlike Twitter, however, Ally McBeal was a product of an America that had not suffered through 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, the ‘08 housing crash, the Trump administration, an ongoing global pandemic, or any of the proving preventable catastrophes that, through sheer force of denial and human neglect at the highest levels of authority, contributed to same. All this shit’s done a number on our national consciousness and one place we could almost-steadily rely on to vent and uplift one another about it was Twitter. (There are a lot of semantic layers to the instinctual inclination to call Twitter a “place,” but that’s for a different kind of essay.)

Watching these characters I remember so vividly from my teenage years struggle with adult issues I understand much better now in an America where so many people felt reason to hope has been hugely emotional for me, even wrenching at times. When Ally McBeal was on TV, my father was immortal, and my biggest problem was that I, like Ally, was hopelessly in love with someone I couldn’t have. (Unlike Ally, though, this was not a former boyfriend and would never be.)

Vonda Shepard, who sang the Ally McBeal theme song, landed a musician’s ideal gig: not only was she responsible for the theme, she also played the in-house musician at the law firm’s bar downstairs, and was often heard accompanying heartfelt sequences to enchance the mood. As fathomlessly sentimental as one of the show’s recoccuring song lyrics may be, I can’t get them out of my head, and they’re too relevant not to share:

Here’s the photo I’ve been looking for

It’s a picture of the boy next door

and I loved him more than words could say, never knew it til he moved away

Faded pictures in my scrap book

Thought I’d take just one more look

and recall when we were all in the neighborhood

Personally, I didn’t grow up in “the neighborhood,” because I’ve been moving around the country since more or less the dawn of my consciousness. The closest I’ve ever had to a neighborhood, meaning that block where you know everybody and everybody knows you, is Twitter. Now, I’d like something closer than that. I grew up believing that every implosion heralds a beautiful phoenix, glowing with the embers from the ash, but I don’t have the hope that I used to, because I seriously thought that’s what 2020 would be for us. It was the Year of the Rat, a legendary trickster starting everything over, and that’s what I believed we would do. I thought it would obliterate our obsession with image and surface because “see and be seen” doesn’t exist when there are no bars, I thought people would look to the disability community and say, “Wow, you had a point about this work-from-home thing you’ve been going on about for years, we’re all collectively very sorry that we doubted you and the wisdom of your non-normative existence.” I thought school children would have the opportunity to learn and explore in different more immediate ways because the rigidity and pointless drudgery of all US school systems would undergo a necessary upheaval, and I thought we would come together, regardless of politics, with a new understanding of how necessary universal healthcare is. In short, I thought we would collectively exhale, all over the world, out of the terrible relief of finally being able to admit that normal didn’t work for anyone.

Instead, we’re here. I had forgotten how much of Ally McBeal’s day-to-day life involved people telling her that she was too much of a dreamer for her own good. Ally definitely didn’t get her worldview from her parents, but I certainly did. My dad died suddenly at age 50 in 2006, almost exactly a year after Katrina, and there is absolutely no way I can sum up my mother currently. What I can say is that they both dreamed colossally. They were such passionate, to-the-core dreamers that they didn’t even call themselves that. For both of them, living in the world meant building on extraordinary visions of what the would could and should be.

My sense is that that used to be easier. But I’m not sure where that leaves us. Hopefully, we’re still moving.