If I were you, someone who reads me regularly, rather than the person who has the dubious pleasure of being me (an alright draw of the cards when you get down to it, but not without its extreme mostly-self-created difficulties) I would be asking, “Sarah, why are you spending so much damn time talking about the 90’s WB Network and what the hell does any of it has to do with disability which is your theme here? It is your theme, right?” and I would tell you that yes, obviously, it’s right there in the title, and the relation to the 90’s WB network maybe an abstract connection, but it’s crucial. Here’s why:

A lot of my unfair and unfounded self-hatred (anyone who’s spent any sustained time with middle-school girls knows that self-hatred reigns supreme and is never fair or founded) went back to a whacked-out notion I had that beauty and romance were closed off to me because my body was inherently hideous. My therapist, who’s also visibly disabled, puts a lot of this down to a dearth of representation in media: how could I know that disability and gorgeousness could go together if I never saw it? and that’s a factor, for sure, but there’s another problem, sigh sigh sigh sigh, and that was my fucking friends. My friends. Were so hot. Like ridiculously hot. Like you don’t even know. I don’t have photos, just take my word for it. Take my word for how often I’d arrive at school on a Monday morning and a boy would say to me, “I saw you at the _________, tried to call your name but you didn’t hear. WHO’S YOUR FRIEND?” I don’t blame them, to be clear. The girls I rolled with were otherworldly. And I was the observer down here on this trash-strewn planet and I would never be better than what I was, and in the manner of 7th grade girls convinced they know a damn thing when they don’t, I cried over this “truth” often (and my dad wrote me a song about wishing he could make me feel better, because…because that’s who he was). But there was one hour I did feel better, when I forgot my every problem or issue and succumbed instead to the electrifying problems and issues rattling the all-too-pretty citizens of Capeside, a fictional New England town.

When I breathlessly said to my dad after emerging from my room in the throes of a particularly stirring episode, I said, “I don’t need a life! I’ve got Dawson’s Creek!” I was only partly joking.

I’m seriously thankful for all of you every day because when I started this endeavor I hadn’t the slightest clue than anyone would actually be reading these essays and I know that you do, BUT no height of gratitude is actually worth re-watching that series, so, right here, before 8am, from memory, I’m going to tell you all of the things that happen in the pilot episode, just the pilot episode:

We find out that Joey (played by a young and pre-Cruised ridiculously pretty Katie Holmes whom we all wanted to be) is living with her sister because her dad is in jail for dealing cocaine. (They make a big deal about the sister having a “Black boyfriend,” which even at the time I thought was weird, because while this is definitely supposed to show us how provincial-at-best Capeside is, Joey never spoke about him comfortably, a fact I’m only just remembering now).

Pacey (Joshua Jackson), Dawson’s best friend, successfully seduces his English teacher, GROSS

We find out that Dawson’s mom, a news anchor, is having an affair with her colleague, and it’s more than a little bit perverse because Dawson, while watching her on TV, jokes to Pacey that there’s something subtly untoward about the way she says, “Back to you, Bob,” and the look in her eyes, then it turns out this is true. Imagine being Dawson’s dad, cuckolded by a Bob, of all things.

We find out that New Girl In Town Jen Lindley (Michelle Williams), Dawson’s immediate first love, lost her virginity when she was 12 and was forced to move to Capeside because her dad caught her in the act and made her go live with her super-Christian grandmother. Relating this story, which she eventually does because Joey’s jealousy renders her a complete pest and Jen tells her the truth to shut her up, parts the seas for the immortal line, spoken on the edge of tears by Jen: “Daddy’s little girl, fornicating before his very eyes.” THAT WAS A REAL LINE THAT A PROFESSIONAL TV WRITER WROTE ON A SUCCESSFUL PROGRAM. It was a simpler time, it was a stupider time, I don’t even know.

We find out that the crux of Joey’s identity lies in her all-consuming crush on her best friend Dawson, about which he is entirely clueless. Nothing will be done about this until the season finale, at which point, the female contingent of De La Salle’s Class of ‘02 will collectively lose our minds. I will come to remember Homeroom discussions of Dawson’s Creek as the only reliable point in my school day in which life was unambiguously worth living.

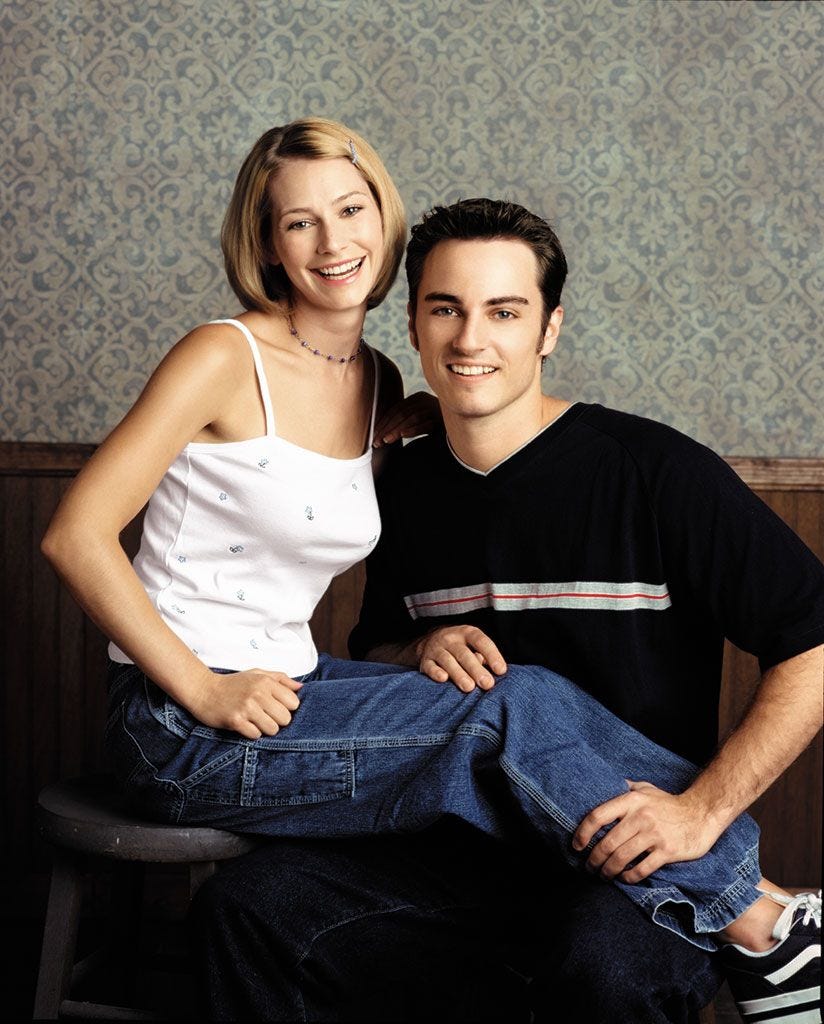

Later, much later, there would be a gay character (Jack, played by Kerr Smith), and there would be a gay on-screen kiss so short a blink made you miss it, and there would be moving discussions about mental illness and treatment between Pacey and his eventual girlfriend Andie (Meredith Monroe), but all that would come later. For our circumscribed purposes here, Andie and Jack are relevant to this essay because one glorious weekend, the weekend of Anne Rice’s legendary Halloween ball that my hot best friend and I were still riding the intoxicating waves of, we saw a hip-looking group of people that included a luminously adorable woman that looked exactly like Andie from Dawson’s Creek, and made the mistake (or so we thought) of saying something to my father, who, ever eager to do anything potentially funny and guaranteed to be embarrassing, rolled down the driver’s side window of his blue Buick and said, “Hey, they think your friend looks like the girl from Dawson’s Creek!”

I was livid and about to rant through my teeth, and then a response came: “She is.”

Well, all my burgeoning shame flew right out that open window and I blurted out, “CAN WE MEET HER?!”

They said we could. We pulled over on Royal St. and it turned out Jack was in the crowd too, but he was so staggeringly gorgeous in person that we hadn’t recognized him from the show: cameras don’t do everyone justice. No one traveled with cameras then and we had nothing reasonable for them to sign, so my best friend searched the thankfully-messy car floor until she found a ripped-open envelope. She tore it into two neat halves, which they autographed with thoughtful inscriptions for both of us.

Homeroom the following Monday was especially electric (and of course I brought that sacred torn envelope to school). Life was emphatically worth living. And I had never been more grateful for my dad’s deliberate penchant for embarrassing me. “It’s my job,” he’d always say. It served us beautifully here.