Getting my MA in Children’s Literature from Hollins University in the late aughts felt like a cross between grad school and summer camp: the low-res program that took place over a few back-to-back summers meant we were hardworking scholars who, between stressing about sources and citations and theses, were also swinging on tire swings and engaging in questionable romances with people from other programs and spending warm nights watching fireflies over expansive conversation. We went to midnight movie screenings, wrote experiments after attending literary talks, and spent nights at the library until closing time, at which point the librarian would ring an actual cowbell. (I thought “at the library until the bell sounded” was a figure of speech until I heard it myself.) We marveled at the ways we felt like we’d found ourselves in a movie or a book, one of those plots centered around the summer that changed everything.

I remember teenage summers with a vividness that surprises me: when school been out for at least a week and the anxiety dreams of unannounced tests subsided, an exhilarated lawlessness took over. For me, that initially meant covert conversations over the still-nascent internet until 5 or 6 in the morning with equally curious strangers who I wished were my boyfriend. Later, it meant sneaking out with the cordless phone to talk on the balcony until 5 or 6 in the morning with my actual boyfriend. One summer, it was visiting my best friend in Colorado where we watched non-parental-approved movies in her wood-paneled basement, again staying up until ungodly hours, that was the important part. When I got to college, I spent summers in New Orleans with my father, but thinking about him right now still carries the weight of a grief that disrupts the “carefree summer” narrative I’m going for.

Maybe it was always an illusion: we are who we are all year long, right? And by now I’ve worked with enough students to know that while, yes, academic stress is a factor in life, it’s never the only one and it’s rarely the most prominent one. Getting rid of the “go to class” imperative is not the same as getting rid of your problems.

Still, everyone is entitled to hope that with the disruption of Schedule comes room for possibility and adventure and romance, and recent studies show that being young right now doesn’t coincide with that hope. I’m not surprised: my heart often breaks for students who’ve written about anxiety so severe it makes them nauseous, about social media being so aggressive in its algorithmic mind-warping that they honestly don’t know what they themselves want or enjoy. They write about being terrified that important medications will be rendered inaccessible and cause serious problems for their health, and about having lived in fear for almost as long as they could remember that the next school shooting will be on their campus.

Where does summer fit into all this? I don’t mean summer the season, though iced drinks and swimming and revealing clothing can all be part of it: I mean summer the break, the break from the stressors that are supposed to be part of the youthful academic year. With the 24-hour news cycle comes 24-hours of warranted concern about everything from these horrific immigration crackdowns to the next defunding of the next program that’s directly responsible for their parents’ jobs. I guess I should add a caveat here: from where I am in rural Georgia, nearly all college students go home for the summer. Athens, Ohio, my nearly-official new home, will, I hope, be more active in this sense. The Midwest isn’t known for its endless variety of hot places to go in the region, so that most young people who’ve found an exciting place to live tend to stay there unless they go on vacation. Iowa City didn’t empty out over the summer — where else in Iowa or Illinois could provide? I’m suspecting that Athens will be the same way, because you can’t tell me that come mid-May, everybody rushes out to Toledo.

Iowa City was also rich in events like summer outdoor concerts, outdoor movie showings, and farmers’ markets, none of which are part of the culture here and all of which I’m expecting to be part of Athens’ cultural fabric. These things can and should still exist, shouldn’t they, as fortifications for our spirits and a means of strengthening human connection?

I often think about how the convenience of remote services has come at the expense of so much human interaction, to our peril. Having a disability that prevents me from driving means I benefit immensely from living in an age where it’s possible to get so much done from home, but I also know that casual interactions can be the difference between depression-as-obstacle and depression-as-tragedy. At the darkest hours in my life thus far, I owed more to movie theater ticket-takers, baristas, and shop clerks than they’ll ever know. Being required to leave the house can be essential to a person’s well-being, a statement that, as I write it, sounds so commonsensical as to not need to be written. But I think it does, these days.

When I lived in Seattle, one of my closest friends was someone I never would have met if I’d owned a printer. He worked at UPS, and having to print out my works-in-progress to present at readings led to a direct discussion of my work and interests which led to a direct discussion of his creative work and interests. (In the intervening years, he went back to his Hawaiian roots and relocated there where he now works as a respected tattoo artist).

We all need people in our lives who hold us at our worst, but we also need people in our lives to whom we always seem easy to be around. Making the commitment to work through mental health issues is the definition of not-fun, so the only way, at least that I’ve found, to make sure it’s all worth it is to get confirmation that the thorniest things about myself are not the whole of who I am. A girl who worked behind the counter at a bakery in Ukiah, California told me that she and I “have the best conversations,” and I still remember everything about that moment almost ten years later because it was such a relief.

Anyway, summer. My father died in July, which means that every delightful July day I’ve ever had since feels like an impossible triumph. But collectively we’ve endured horror after horror over summers: the killings of Mike Brown and George Floyd and too many others at the hands of those who’ve pledged to serve and protect, COVID lockdowns that we’re still recovering from, and awfulness that, while small-scale in itself, point to yet more systemic issues. Last July, the allegations against Neil Gaiman broke for the first time, and his trial date is now set for July of 2026. (Considering how few civil cases go to trial, this will be historic if it does). As I write this, protesters are meeting the moment at a monumental height in Los Angeles and Pride parades, after years of being subsumed by corporate sponsorship, are back to being the determined liberation acts they once were, or so it seems. Summer.

Reminiscing about summer jobs feels quaintly twentieth century, but my first one was at a movie theater and we had to watch an Orientation video that showed us the ropes. Speaking about appropriate workplace behavior, a woman with rosy cheeks and wavy blond hair told us that, “As you get to know the people you work with, you’ll probably meet someone that you’re attracted to.” I was distracted for the rest of the video thinking that sounded impossibly optimistic. Some people are more crush-amenable than others and I fall on the “highly susceptible” side of the spectrum; still, I don’t remember being attracted to any of my fellow ushers, and I can’t remember any stories of them being attracted to each other. The little vests might have dulled our appeal.

The summer before my senior year of high school, I had to take a summer Geometry class in order to come through with my plan to graduate early. The class took place Monday-Friday for — I can’t believe any of us, the teacher included, agreed to this — five hours. On Fridays, we would use the final two hours to watch an inspiring school-related movie like Stand and Deliver. Still, five hours is a very long time, and when I lamented about this fact, I was given unexpected advice: my friend asked if there was a vending machine in our classroom building. There was. Did it have Peanut m&m’s? Of course it did.

Instructions: “Put one Peanut m&m in your mouth while looking at the clock. Don’t bite — keep sucking on it for five full minutes. Once five minutes have passed, do this with the next Peanut m&m. It’ll make the time go faster.”

Here’s the wild thing: it worked.

Admittedly, I haven’t attempted it since, likely because most adult obligations come with the understood mandate to pretend like you think this meeting or Professional Development seminar or Orientation is entirely worth your time. Sucking on a Peanut m&m with fervor while staring at the clock is frowned upon. Amazing what we can get away with when we’re not expected to have developed frontal lobes.

The low-residency summer program in Roanoke, Virginia where I got my MA still exists, and it should then follow that scholars and artists are still swamped with chosen work and awed by the fireflies and planning their costumes for the traditional Halloween in July party, celebrated long before Summerween became a trend. One of my students wrote a persuasive essay about how dating apps have eroded intimacy and the younger generations’ understanding of love, which makes me worry for, among other things, summer romances. Not climate-change worry, just human-thought worry. We need all the connection we can get.

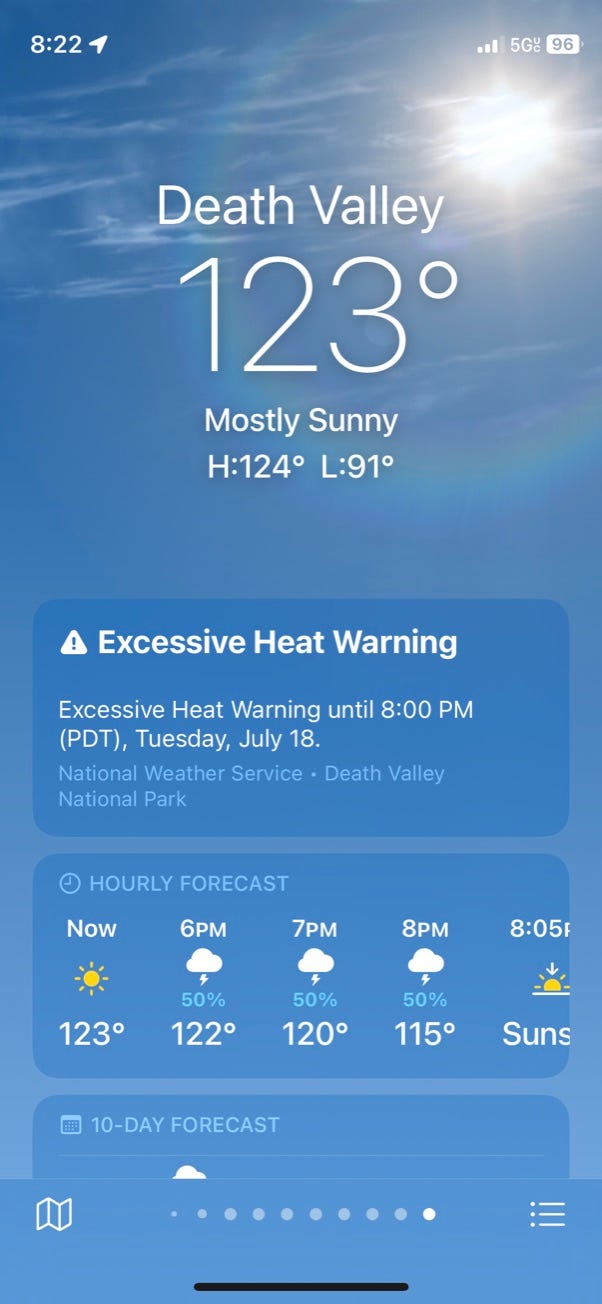

If you’re going somewhere this summer — especially if it’s a place that makes clear to your mind body and spirit that it’s summer — I would love to hear about it. If you have specific songs you listen to, books you read, movies you enjoy when this season hits, I would love to hear about those too. And if you’re in Australia, apologies! I didn’t mean to leave your hemisphere out of this conversation and I hope you’re warming up. Comfortably, I mean, not in the Death Valley warning sense