My cousins new about the premiere of Disney’s The Little Mermaid before I did, and I don’t know who alerted them to this marine adventure, but we knew, before we saw it, that we loved mermaids, that we wanted to be mermaids. (Last I checked, that was more or less still true.) We didn’t know about Hans Christian Andersen’s original story, or the statue in Denmark, initially built to commemorate Andersen’s martyr-heroine but so often defaced by feminist activists that it’s hard to find a photo without graffiti’d adornments, but all that knowledge would come later. I would grow up to essentially devote several eras of my scholarly life to Andersen’s story, but at this point in the process, I was six.

There was no such thing as Disability Representation in 1989 — the ADA hadn’t even been passed yet — so I was not concerned about seeing a Disney princess on crutches; that would come later too. The representation that validated my existence was the one that took me beyond my fantasies of being blond — blond like Barbie, blond like Princess Aurora, blond like my friends’ prettiest babysitters — all of a sudden, here she was, a Disney princess that had RED HAIR. My hair in those days went past my waist, and the only people who complimented it were old ladies in the grocery store. I was alerted by a hairdresser who listened to my childhood laments that when I grew up I would discover a world of guys who preferred red to blond, and I was precocious enough to, well, to borrow a phrase, wish I could be part of that world.

So Ariel had red hair and wore a purple shell bikini top and had a green tail, which means that if I was going to step into my own as A Girl Who Would Not Be Ashamed of Her Hair for At Least 90 Minutes, I would have to wear a purple shirt and green leggings. At six years old, every age over seven seemed ancient, so when Ariel yells to her terrifying and borderline-abusive father King Triton, “Daddy, I’m sixteen years old, I’m not a child anymore!” we believed her: she wasn’t. She was a grown adult who should have full control over whom she was going to marry, and when, and on what this assertion that she and Prince Eric are soulmates should be based.

If you’re familiar with this animated film you know that there is everything wrong with this alleged love story in which a dude falls for literally just-a-voice and a girl falls for literally just-some-looks, and while we’re at it the colonialist implications of Sebastian the not-actually-Caribbean-but-playing-it crab warrant an essay in and of themselves (and such essays have been written). My mother engaged me in conversation at length about how giving up your voice for a man was the worst thing a woman could choose to do and these conversations around Disney movies were the reasons she allowed me to watch them. But on that day in 1989, I wasn’t thinking about those conversations: I was simply enthralled by this red-haired mermaid with the life-changing voice who wanted something impossible and stopped at nothing to get it. The red-haired mermaid with the life-changing voice who found depth and mystery in objects that a lot of humans would’ve overlooked or even thrown away.

what’s a fire, and why does it, what’s the word? burn

What I felt, even if I didn’t consciously see it yet at that young age, is that here was a story of a red-haired girl so determined to live her life differently from the one her family planned out for her that she’ll travel down to forbidden depths — the sea witch’s unmistakably vaginal cave — and take risks. Give up the thing she’s been praised for all her life, the thing her family has built her sense of worth around, just to explore a foreign world she knows absolutely nothing about.

“You are hopeless, child,” Sebastian tells her once she has achieved her inexplicable goals. “Completely hopeless.”

From an Establishment standpoint, she is. By any other lens, she’s the only character we meet who does have hope.

It was all these things — and also the way Ursula refers to her pet/minion eels Flotsam and Jetsam as “my poor little Poopsies,” which in her bellowing and mighty voice we thought was the most hilarious moment possible — that changed my life that day in 1989.

I didn’t know how much, though, until I got to grad school and morphed into an absolute fiend for fairy tale scholarship: any and all, really, but unsurprisingly my focus was on Hans Christian Andersen. As a bisexual writer who spent his life ashamed of his physical appearance, he would likely be surprised that so much of the discourse around this fairy tale centers on its supposed anti-feminist sentiments (because a woman suffers for a man) because he’s quoted as saying that he sees himself in his mermaid: he was in love with a man who wouldn’t look at him, as though they were from different worlds, and perhaps he would have suffered knives-through-your-foot-at-every-step the way she did, just to get him to compliment his dancing.

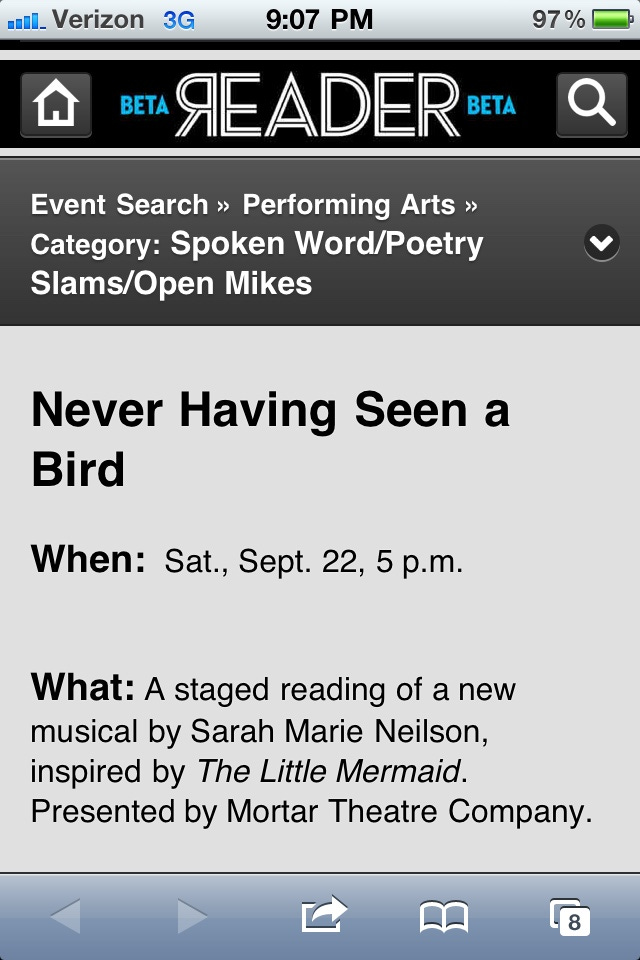

The Children’s and YA Lit program at Hollins University allows even MA nerds like me to do a Creative thesis if we so choose, but it has to have an academic component, so along with my 20-page Jungian interpretation of the Disney version, I wrote a musical retelling of Andersen’s original called Never Having Seen a Bird.

In it, the mermaid is on crutches when she emerges from the water, which only makes sense if you’ve never walked before. As in the original, her steps cut like knives, but they’re worth it (she’s not afraid of pain). After she successfully seduces the prince, she gets her voice back by means of her first orgasm, and dynamics shift swiftly after that.

We performed it as a staged reading in Chicago, and the only issue with the Pegasus Players’ extraordinarily talented group containing Equity actors is that it means I can’t show you any of it because of contractual issues with filming.

Anyone who knows Andersen’s story knows that the Mermaid’s family is matriarchal down to the core, with no talk of a father or a king. She learns about the human world from the stories her Grandmother tells to her and her sisters, and the title of my musical came from her stories about “singing fish that live in the trees.” The narrator explains that “The Grandmother called the birds ‘fish,’ because if she had said ‘birds,’ the little mermaids would not have known what she was saying, never having seen a bird.”

I am no longer attached to a redheaded mermaid: I couldn’t be more excited to see Ariel portrayed by the transcendentally beautiful Halle Bailey, whose singing voice could certainly inspire a prince to settle for none but the one with those pipes. What are we going to do with Sebastian in 2022? Well, despite the near-lifelong love that I just can’t shake for the undeniably sexy number, “Kiss the Girl,” I remain skeptical that even Lin-Manuel Miranda can save that character. But we’ll see! Or at least, I certainly will. They had me once, and they’ve got me again.