In 2018, I was working as a substitute teacher in Salinas, CA, and had the tremendous fortune of filling in for a high school Drama teacher close to Halloween. The juniors and seniors were collaborating on a haunted house, an immersive experience offered in the school theater during the week leading up to the holiday. I was astounded enough by that school’s theater space to snap awed photos before students arrived:

Working with Salinas’s crazy theatre kids and watching them work together made my year. It wasn’t just the soul-familiarity of the vibe and that surreal warm-heartedness that comes from being on the Adult Side of the scenario so integral to your own youth, though there was that. What nearly brought tears to my eyes was how passionate the students were about creating a legitimately terrifying haunted house for their peers to remember. This was in the days before TikTok took over — there was no notion that their efforts could make them famous. It was simply that an unforgettable Halloween for the collective good was vital. They had to do it right, and they set to work and discussion and creation like nothing mattered more. Because, in that moment, nothing did.

A couple weeks later, I got to witness the fruits of their gratifying labor and I still shudder to remember their achievements. I was too chickenshit to get on-stage for full horror immersion, which I’m not embarrassed to say, because while I observed from the back, an all-too-convincing Pennywise leapt out at his peers, sending a student shrieking out of the theater. That could’ve been me.

I’ve been thinking about youthful artistic collaboration ever since the untimely death of my dear friend Arlen Lawson, who astounded audiences with his own playwriting and acting talents when he wasn’t much older than those high school students. A touchstone of my college experience was No Shame Theatre, a weekly showcase of short student-written pieces that sought to push every boundary we could think of. We worked on our scripts all week, then cast and presented them as on-book performances starting at 11pm every Friday night. Like the Salinas high school students, we had a legitimate theater space in which to make our art come alive. There was no budget, but there was a lighting booth, providing darkness between pieces and mood-setting when needed. To the extent that No Shame was relevant to our future ambitions as artists, it was as an incubation room. Some of our monologues and scenes developed into full-length plays, but that was as far as we were looking. What mattered then was making art now.

After college, theater became about career. A lot of people I knew moved to LA, several of them Made It, several more are making it work. I haven’t talked to them about the work they do or whether they get high off their current projects the same way they did when they were locally-beloved week-to-week performers. Ani Difranco once asked if big stars look longingly back at earth. (In a live recording, she poses this question in a lyric and an audience member shouts, “NO!”)

I’m thinking less about reach, though, and more about the notion of coming together to work on something for the sole reason of caring about it that much. During the undergrad semester that I wrote my first full-length play (which, as it happens, starred Arlen Lawson and began as a No Shame piece), I was taking reduced hours to get residency for in-state tuition. My only class for that glorious stretch was the Independent Study that culminated in the production of that play. (It was a 19th-century period piece, so there was plenty of course-friendly research to be done. It was also a very gay play in which Oscar Wilde played a prominent off-stage role, and my instructor was well-respected for her scholarship in Queer Studies and Theatre, so this all gelled beautifully.)

In addition to the main stage and second-stage productions expected of a healthy University Drama program, Theater Life in Iowa City was defined by two annual events. The Undergraduate Ten Minute Play festival had a faculty advisor who selected its plays from dozens of submitted scripts and who made sure nothing got out of hand, but the 3-day run was written, acted, directed, stage-managed, etc. entirely by undergraduates. The New Play Festival, a week-long wild ride of staged readings by day and productions by night, featured original plays all written by the Playwriting MFA students, directed by the Directing MFA students, and cast with an impressive mix of undergrad, graduate, and community actors.

I don’t remember anyone talking about what they hoped all this would lead to. Of course it led to a fair bit: those MFA Playwrights went on to fill impressive resumes and so did the actors, but in those moments leading up to production, no one was asking, “where will this go?” All they wanted was for it all to go spectacularly. And it did, even when one cast member’s leather pants ripped in the crotch mid-performance during the Ten Minute Play Festival, and, owing to the leather’s tightness, said cast member wasn’t wearing underwear. The play was comedic, mercifully, and the innocent line scripted right after the rip was “I showed it to everyone.” The audience roared, and the show went on as the star gamely employed strategically placed yet natural gestures. He came out during curtain call wearing jeans and dancing flamboyantly as another cast member slipped dollar bills into his waistband. (The playwright expressed gratitude for a comedic moment that “I couldn’t have written any better.”)

My first publications came from that festival because a company specializing in anthologies for schools/student actors scoped our productions to buy rights. The theater was packed. But when something matters to you that much — and the Ten Minute actors rehearsed tirelessly — you’ll just make sure it goes well, even when it doesn’t.

I don’t think the admirable ability to laugh even when a high-stakes mishap takes place is specific to youth. My dad could do it. Other people did it more easily when he was around. But I think a specific kind of confidence is possible when you know you’ve been working as hard for something you care about as other people have. When, in short, you know you’re not alone. There’s a lot of power in the plural yours.

The most potent non-death-related grief I’ve yet contended with is the loss of someone I once felt like I was writing with and for. Expecting an MFA program to replace what I got from that relationship was like realizing too late that a Band-Aid has been dipped in salt. I get attentive helpful feedback from everyone I’ve met on everything I do, and I strive to be that helpful to others. But we’re not working on different facets of the same thing. The support is genuine, but our missions are solitary. That makes for invigorating workshops. That helps produce strong work. Varied perspectives can only be helpful. But I’ve temporarily lost the love of the process for its own sake.

“You have to learn to write for yourself,” my therapist says, in that sensible tone people use for self-evident truths. That sounds like an answer, and it also sounds boring, lonely, unfulfilling, and pointless. I don’t remember being so invested in my own fictional characters that I could keep going from sheer auto-adoration, so intrigued by my own made-up stories that I couldn’t wait to get all their brilliant twists down. Yet that was me. Even though a script is just one facet of a play, I wrote that full-length period piece because nothing mattered more. I woke up every day exhilarated: I get to write this.

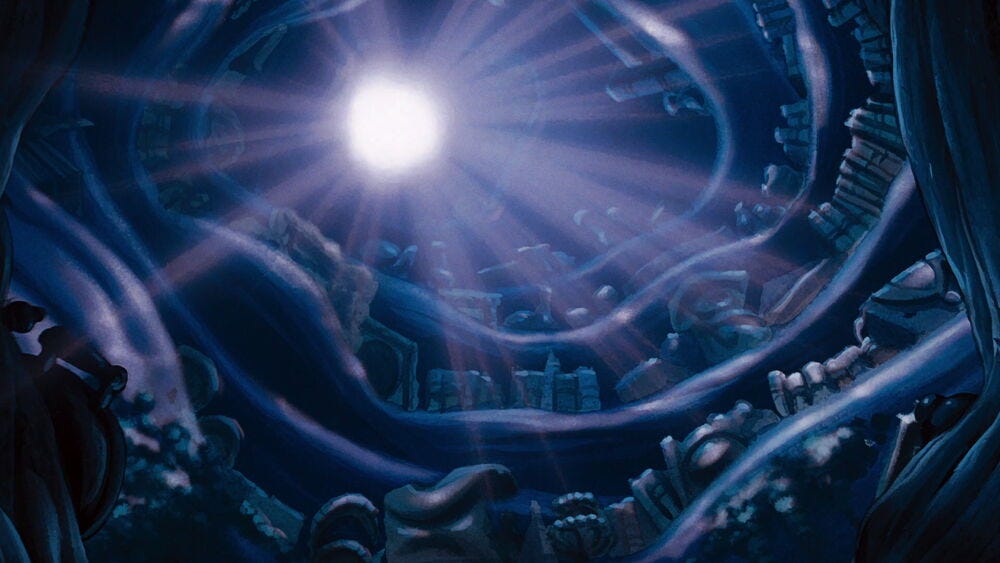

I also got to do a lot of other things to make that play possible. In addition to nerding out about 19th century bohemian culture, I wrote a grant to help cover production costs and did aughts-internet research that led me to Alfonso’s Breakaway Glass, from whom I ordered a prop Absinthe bottle that Arlen dutifully lunged at a wall during the climax of the play. I got permission to raid the University’s majestic prop room and felt like Ariel rhapsodizing in song about her collection of human objects:

I came away with elegant flasks and a giant paint palette and other enlivening sundries. An artist friend painted a portrait of one of the lead actors because like any young Oscar Wilde obsessive I had to make a portrait integral to the play, ominously yet seductively observing the action from its deceptively still canvas. That artist also helped me design my promotional fliers and paper them all over town. I think I felt something akin to what the young designers of that Salinas High haunted house felt: this is an occassion, and many of us are at work on it, and it matters it matters it matters it matters it matters it matters it—

Over the years I’ve chalked the elusiveness of that feeling up to Hurricane Katrina and my father’s death and the rise of school shootings and climate change and all manner of internal and external disasters that could make you question the point. But even when I feel at peace, something is missing. Maybe that’s good. Maybe Make It Matter is the ultimate cosmic writing prompt and I should be grateful for this weird gnawing space in my chest from which I had a brief but powerful respite. Little in my life was going smoothly when I felt like I knew why and for whom I was writing. Everything is better now, including my sleep.

So why do I go through pages and think “Fuck is all this for?”

Maybe answers aren’t the answer. My definition of “artistic collaboration” might be too narrow for my own good. High school and college offer structured ways to come together and make something, and every campus is a dome in which the micro-actions of a group take on intoxicating importance. Am I conflating a feeling that something matters with not having room to breathe? I live in the middle of nowhere which sometimes feels like too much room. Maybe I just need to stretch.

I guess the prompt is, “Make it matter. Fill the space.” I’ll try.